I've Seen This Before

My first encounter with programming was at a flea market in Mexico City. I was maybe 13. My dad and I were walking through rows of pirated CDs when one caught my eye: Borland C++. I asked the seller what it was. He said it was a program to create other programs.

That blew my mind. But I honestly don't recall understanding what he meant.

My dad bought me the CD. I went home, installed it, opened it, and nothing. I had no idea what to do. I didn't know what a programming language was. I didn't know about syntax or compiling. I was disappointed, because I knew that was potentially a powerful tool, but I had no idea how to use it.

In Mexico City's metro, I'd pass by magazine stores selling computer magazines. One day I found a C++ book in Spanish. I read it without ever running the code on a computer. But then I started to understand how I could tell a computer what to do, how we could have an agreement of what a car object was. And how we could do something to that car.

Then came Java at university. Then C. Then C#. I learned a lot of programming languages, I loved learning the different paradigms they offered and building small programs. But, to me, it was always the same: learning another way to tell the computer how to transform data.

At some point, I discovered XNA and started making games. Back in college, when I wanted to make games, people would tell me to do it from scratch, to use C++ and OpenGL. I tried, but it was a lot of work. XNA helped, but then a friend showed me Unity, and that was another great discovery. Unity could abstract things that XNA didn't, such as physics, model loading, animations. Now, I was closer to my goal: making games. Not writing a game engine.

I wrote shaders by hand. I loved designing them, but the typing was just a means to an end. Then Unity introduced Shader Graph, and I never went back. Nobody called me a fake shader programmer. (Or maybe someone did, but I didn't hear. And probably would not care.)

The same thing happened with game engines. People used to insist real developers wrote everything in C++ from scratch. Now engines are standard. We forgot the argument. Kind of. Now the argument is which engine is best.

I've watched this pattern repeat many times. Something new comes, and there's an urge to decide whether we like it or not. Cell phones, operating systems, game consoles, frameworks.

The Debate

In the world of AI, I see two timelines. B.C. and A.C. Before ChatGPT, and after ChatGPT. The AI concept became mainstream and was no longer a thing only a few could use, but something almost every human had access to.

But even defining AI is challenging. And probably there's no wide agreement on what it means. Is ChatGPT equals AI? Is the transformer architecture? Are LLMs in general AI? I think AI falls into the same bucket as other controversial topics such as social media, vaccines, immigration, and many more that have had humans divided for all of our history.

The debate I see is either: "anti-AI", or "pro-AI". Going from "AI is our salvation" to "AI is the worst thing that has ever happened." It is very rare to read something in between.

Why? Because dividing the opinion ignites the algorithms. Because it makes debating easier, it's not about being open minded and open to changing your mind, but about being as vocal about your point of view as possible, so content gets to people who want to hear that. And it's easier to sell whatever you sell. If you are pro something, you cater to that market. If you are anti something, you cater to them. Rather than trying to sell to everyone.

This goes way back. Humans thought the earth was flat, that the earth was the center of the universe, and each time, there were two sides. Look at politics, the same happens. But reality is way more complex than a simple black and white.

I want to offer a third option. Not pro-AI. Not anti-AI. Just: try it, and decide for yourself.

In this article, I want to focus on what I know, which is Software Engineering and Game Development. But I'm very positive that the same applies to other areas of the economy.

What Changed For Me

Many years later, I discovered ChatGPT. I went from using Google to almost entirely asking ChatGPT to search for me. And I started hearing people talk about Cursor and Windsurf, but it didn't immediately click in my mind how they could be used to write code. I had used ChatGPT once or twice to help me write functions or short scripts, but I couldn't tell what the AI was doing versus what I was supposed to do.

Then I tried Claude Code. And it clicked.

The way I see it, programming has two parts. One part is thinking: solving problems, designing systems, deciding what to build and why. The other part is typing: syntax, APIs, boilerplate, looking things up in documentation.

When I started using Claude Code, I realized: I want to tell a computer to transform data. The language is irrelevant, and if I can do it with a language I already know, English, then there's one less layer between my brain and the computer. It was another dejavu, just like XNA to Unity to Shader Graph, each tool removed a layer between what I wanted to do and the doing of it.

I've outsourced the typing to AI. The thinking is still mine. I still need to guide it a lot, it's not perfect. But there's no way I could have built what I've built with Claude Code in a year, on my own.

And that's where the real value showed up. Not just building faster, though that's part of it. The real value is knowing what not to build. I had ideas I'd been carrying for years. Gameplay concepts. App ideas. System designs. Things I thought were good but never had time to build properly. With Claude Code, I could prototype them fast, test them, and see if they were worth pursuing. Most weren't, but now I could take them out of my system faster. Ideas I might have spent years on, I could kill in days.

The parts I enjoy are still mine. If anything, I do more of that now because I spend less time on the rest. If you love typing code, keep typing. If you love learning language syntax, keep learning. Use AI for the parts you don't enjoy. Or don't use it at all. That's fine too.

The question isn't whether the tool is good or bad. The question is whether it helps you do what you care about.

On Art

I love looking at art. Museums, Twitter, books. I'm not an artist, so when I see something beautiful, I wonder: how did they make this? What were they thinking?

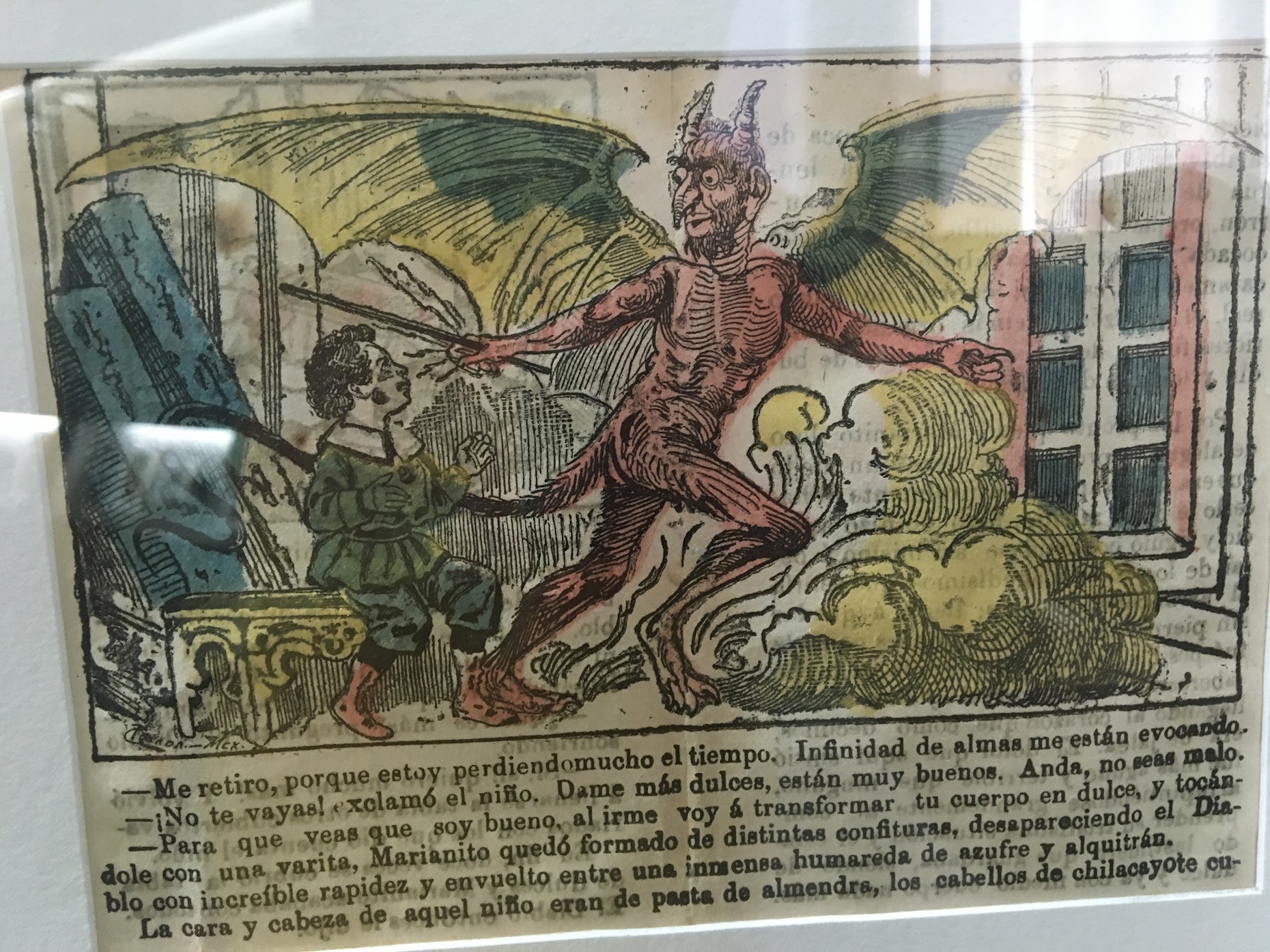

AI-generated art (maybe we should not use the word Art yet?) doesn't hit the same way for me. When I look at it, my brain just thinks: that this is a prompt that converted noise into an image. Yes, you can trick me, but that's more on you than on me. Humans, we are easy to trick.

Something similar happened with CGI. When I was younger, I'd watch movies and wonder at impossible things. I remember watching a TV Show on Discovery Channel Latam, "La Magia del Cine" (Movie Magic). They showed how special effects, puppets, camera tricks, etc, worked. Then I learned how CGI worked, and some of the magic faded. It's still impressive, but different.

Maybe one day I'll connect with AI art. Today I don't.

We get to choose what we consume. That's a kind of power. But the choice should come from what we actually want, not from what someone told us we should want.

Conclusion

I don't think we will ever agree on a single thing. At the end of the day, some people will take one side, even if they don't fully believe it, just not to agree with someone they don't like. I think there will always be debates, and I love that, about technology and science. What I hope is that as much as possible, we can form our own opinion based on experience, rather than on blindly trusting what others tell us.

Whenever someone tells you:

- "AI is bad, don't use it, reject it." Do they benefit from you not using these tools? Maybe it is a competitor who's using AI, but doesn't want you to, so they take an advantage over you.

- "AI is the best thing ever, if you don't use it you are not going to make it." Do they benefit from you using these tools? Maybe they sell services and they win if you use it.

At the end of the day, look at what improves your life and the life of those around you: humans, animals, and machines. And try to do things in good faith.