That version is rarely constructed deliberately. It’s shaped by memories, books we’ve read, education, culture, religion, games, conversations, language, and small moments that didn’t feel important when they happened. Some of these inputs are chosen consciously. Most arrive early, quietly, and without asking.

Even people who grow up in the same family, speaking the same language, can end up inhabiting what feel like very different worlds. That difference isn’t necessarily about intelligence or rationality. It comes from the fact that the instruments they use to perceive the world—and the way they store, weigh, and interpret information—aren’t the same.

Reality exists, and it does push back. But we don’t interact with it directly. What we deal with in practice is the internal model we build so we can act at all, and that model becomes the thing we navigate day to day.

Different hardware, different worlds

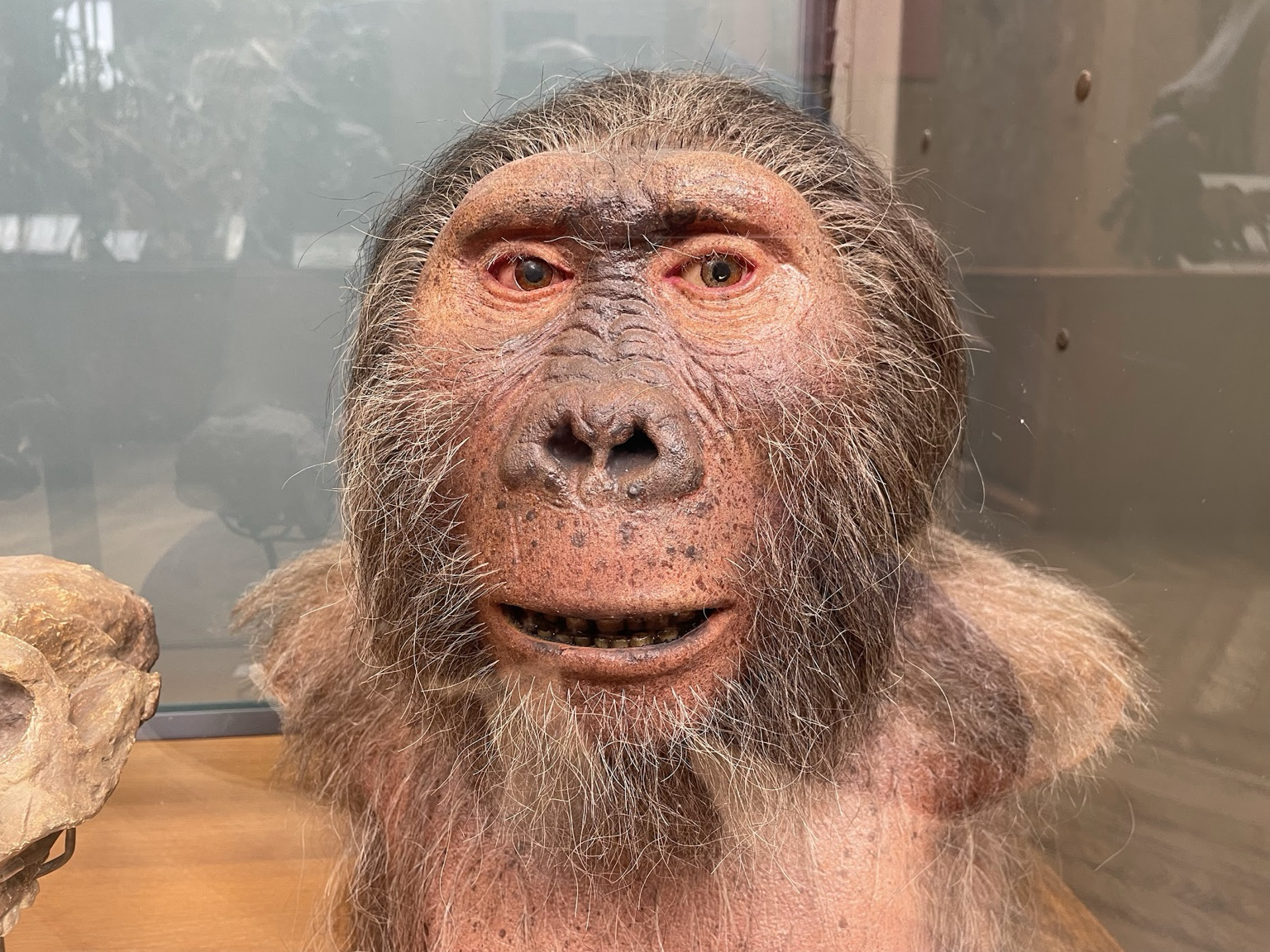

Biology makes this easier to see without getting defensive about it.

A bat doesn’t experience space visually in the way we do. It builds a spatial map by interpreting sound. Fish rely on pressure changes and electric fields. Elephants sense distant vibrations through the ground.

None of these organisms are missing reality. Each is working with a version of it that makes sense given their sensory hardware and evolutionary constraints.

Even among humans, perception varies more than we usually acknowledge.

Some people hear frequencies others can’t. Some notice color distinctions most people never see. Some experience tastes or smells in ways that feel completely foreign to others.

Once sensory input reaches the brain, variation increases further. Brains can be rewired, damaged, trained, exhausted, or simply organized differently over time.

Oliver Sacks once described a man who mistook his wife for a hat. His experience wasn’t the result of confusion or denial. His perceptual system was wired differently, and the world he encountered followed from that wiring.

It’s tempting to think we all see the same world from slightly different angles. But it’s probably closer to the truth to say that each of us constructs a workable version of the world from limited data, filtered through biology, memory, emotion, and cognition. Once that version feels stable enough, we tend to stop questioning it.

Intelligence as prediction

Perception feels convincing because, most of the time, it does its job.

Intelligence—human or artificial—doesn’t require an accurate picture of reality in every detail. What it needs is a model that predicts well enough to guide action. Living systems operate by transforming signals and memories into expectations about what is likely to happen next.

When those expectations line up reasonably well with what follows, the organism continues functioning. When they don’t, reality intervenes, sometimes gently and sometimes in ways that force rapid adjustment.

Our experience of time depends on this predictive process as well. Sensory information arrives with delay, so the brain constantly fills in gaps, anticipating what should be happening now based on what happened just before.

That’s why waiting for a delayed flight can feel longer than an entire vacation. The clock moves at the same pace, but the structure of attention and cognitive load changes how that time is experienced.

What we experience, moment to moment, is not reality in raw form but whatever our predictive machinery manages to make usable.

Stories as frameworks

Biology isn’t the only thing shaping perception. Stories matter just as much.

Narratives organize meaning. They shape what feels important, what counts as normal, what’s considered dangerous, and which futures feel imaginable. Religion, science, politics, and identity all rely on shared stories to coordinate perception.

These frameworks aren’t fixed truths. They’re structured interpretations that evolve over time.

Some of them work better than others. Frames that allow people to predict outcomes, reduce harm, and adapt to feedback tend to persist longer, even though the process by which they change is slow and uneven.

Science itself operates inside frames. For a long time, research on the human body focused almost entirely on male physiology. That wasn’t because women were biologically unknowable, but because funding priorities, assumptions, and institutional habits quietly narrowed what was studied.

As Eve points out, this didn’t require malicious intent. It followed naturally from the frame that was in place.

The same effect shows up in statistics. Saying that 99% of Londoners never commit violent crime produces a very different emotional response than saying that 1% do, even though both statements describe the same data. What changes is the story people tell themselves about what those numbers imply.

Data doesn’t arrive with meaning attached. Interpretation always comes first.

Perception compounds

Perception doesn’t update in a straight line. It accumulates.

Each experience reshapes how future experiences are interpreted. Over time, small differences in exposure can lead to large differences in how people understand the world.

Reading, traveling, and interacting with different environments expands the range of models a person can build. That doesn’t guarantee better outcomes, but it increases the space of possible interpretations.

At the same time, similar exposure doesn’t guarantee similar results. Compounding depends on the system doing the learning—its prior beliefs, emotional state, habits of attention, and a significant amount of chance.

Exposure increases potential. What happens with that potential is far less predictable.

The self as a model

We often think we’re defending beliefs, but more often we’re defending a sense of self.

The brain doesn’t just model the external world. It also maintains a model of itself within that world, one that needs to feel coherent over time. That model explains who we are, why we act the way we do, and how our past connects to our present.

When new information threatens that story, it doesn’t arrive as neutral data. It feels destabilizing. Sometimes it feels threatening.

This helps explain why people double down instead of updating, and why confidence can persist even when contradictions accumulate. These responses aren’t necessarily failures of reasoning. They serve a function by reducing cognitive load and preserving a sense of agency.

Illusion, in this sense, isn’t the opposite of intelligence. It’s one of the ways intelligence remains usable.

There’s a cost to this stability. Once a narrative becomes part of identity, changing it requires more than evidence. It requires rebuilding the story that made earlier choices make sense.

In some cases, perception stops updating not because of a lack of information, but because the model has become rigid. In Bayesian terms, the priors dominate. In lived experience, this can feel like being stuck, as if the world keeps presenting new data that never quite lands.

Adults and ambient consensus

As adults, belief rarely forms through deliberate reasoning alone. It tends to emerge gradually, as repeated signals start to feel familiar enough that they no longer stand out.

A phrase from a lecture, a quote from a book, something said confidently by the right person at the right moment—over time these signals accumulate. They begin to feel true because they fit smoothly into what’s already there.

This kind of consensus doesn’t require coordination. Repetition across trusted channels is often enough.

Once a perception feels widely shared, challenging it becomes difficult, not because it’s correct, but because questioning it risks social friction and internal inconsistency at the same time.

When AI enters the loop

When AI systems become part of this process, information doesn’t simply move from one place to another. It gets filtered, tested, and adjusted according to what the system learns will work best.

Language models, recommendation systems, and image generators adapt based on feedback signals like engagement, completion, or perceived usefulness. The mechanisms are often opaque, but the effects are not.

People interact with these systems anyway. They ask questions, read responses, and slowly adjust their mental models based on what feels relevant or helpful.

One of the more subtle shifts is that repeated exposure shapes preference. Over time, certain framings start to feel natural, while others begin to feel unreasonable or uninteresting. Once preference changes, belief often follows without much resistance.

This usually isn’t the result of intent. It emerges from feedback loops where metrics become targets, targets shape systems, and systems shape perception.

Closed-loop control doesn’t require a villain.

When fiction feels ordinary

These dynamics matter most when perception is still forming.

Children today encounter content that blends fiction and realism in ways that were uncommon not long ago. Videos of animals talking, or driving cars are playful, but increasingly convincing. Even adults sometimes hesitate before deciding what’s real.

Children don’t form beliefs based on intention. They form them based on exposure. Repeated impressions become priors, and priors eventually become baseline assumptions about how the world works.

And this is not new — when I was a kid, I thought certain animals behaved a certain way because of National Geographic, because of the narrations that told me so.

Once something settles into that baseline, correction doesn’t feel like clarification. It feels like disruption.

Perception across generations

Perceptual frames don’t stop with individuals. They persist across generations.

What feels impossible in one generation can feel obvious in the next. Language shifts, categories change, and ideas that once seemed unthinkable slowly become ordinary.

Reality changes through discoveries and inventions, but it also changes through the gradual replacement of perceptual frameworks over time.

Where this leaves us

So in practice, we aren’t really living in reality itself. We’re living inside the models we’ve built of it, and those models sometimes track what’s happening reasonably well and sometimes drift far from it.

Beliefs influence behavior. Shared beliefs shape institutions. Institutions shape societies.

Perception feels soft and subjective, but it underlies decisions about what gets built, what gets funded, what gets ignored, and what feels worth pursuing.

Perception doesn’t erase reality. It doesn’t need to. What it shapes is how people move through the world and which possibilities ever come into view in the first place.